While the First World War was fought overseas, it had a huge effect on daily life in towns like Huddersfield and across the UK. Those who stayed at home were expected to support the war effort in many ways. Families faced hardship, rising prices, and shortages of everyday goods. By the end of the war, food rationing had been introduced to make sure supplies were shared fairly.

In Huddersfield, women quickly stepped in to replace the men who had gone to fight. They began working in industries that were once only open to men. Women ran public transport services, sorted mail in the postal service, and took on vital roles in local factories. They also helped raise funds for war charities, often led by the mayoress. These fundraising events supported wounded soldiers and their families.

Local factories played a key role in supporting the war. Huddersfield's textile mills began producing khaki cloth for army uniforms. Chemical factories, such as Holliday & Co in the area, switched their production to make explosives and other war supplies. Across the country, other workers kept munitions factories, shipyards, and farms running to support the nation and its armed forces.

Although they were far from the front lines, people on the home front still lived with fear and uncertainty. Some coastal towns experienced German bombing raids, and communities across Britain were encouraged to take precautions such as dimming lights and avoiding large gatherings. Even in Huddersfield, the war felt very close to home.

The efforts of ordinary citizens were seen as vital to the war. Life during this time became known as the home front, reflecting the fact that the war could be felt in every home, workplace, and street.

Refugees

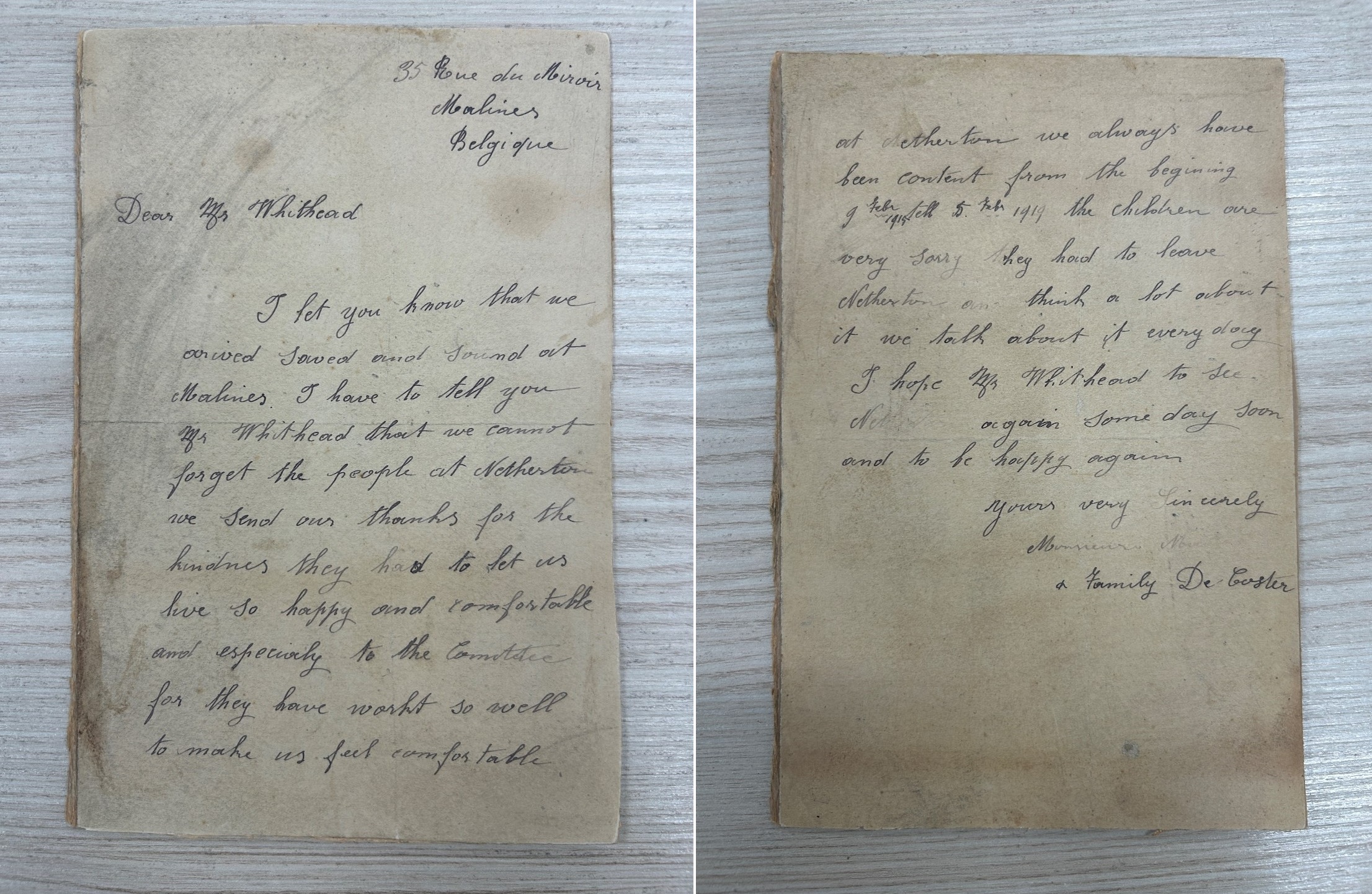

During the First World War, many Belgian people fled their country because of the German invasion. Around 250,000 Belgians came to the UK to find safety.

Huddersfield was one of the towns that welcomed these refugees.

Local groups in Huddersfield helped to support the Belgian refugees. For example, the Belgian Refugee Clothing Committee, started in September 1914, gave out clothes to nearly 500 people and handed out more than 26,000 items by June 1915. Another group, the Honley Belgian Relief Fund, helped families who settled in the area, with some living in houses on Westgate and Eastgate.

Many Belgian refugees stayed with local families and became part of the community. In nearby Slaithwaite, Belgian children went to special classes at St Paulinus RC School in Dewsbury, where they were also given meals by the local church group. In the Colne Valley, a group of Belgian artists set up a community at Blackrock Mills.

One refugee was Josephus Van Camp, a Belgian carpenter, who lived in Huddersfield with his wife Bertha. He worked at Crosland Moor airfield, helping to build buildings and repair aeroplanes.

At first, the Belgian refugees were warmly welcomed and supported by local people. However, as time went on, some refugees faced difficulties. Like other immigrant groups, some were unfairly accused of not helping in the war effort.

The Defence of the Realm Act

To help manage the country during wartime, the government passed a new law called the Defence of the Realm Act, or DORA. This law gave the government special powers to control many parts of everyday life. Some of the changes were sensible, others seemed unusual or even unfair.

Pubs had to follow strict rules. Opening hours were cut to just five and a half hours a day, and they had to close by 9 p.m. Pubs were not allowed to open on Sundays, and beer was watered down to reduce its strength. People were no longer allowed to buy rounds of drinks for friends, to try and limit excessive drinking and keep workers productive.

DORA also introduced some strange rules. Feeding ducks was banned, as it was seen as a waste of food. Flying kites and lighting bonfires were also made illegal, as the government feared they could be used to send messages to the enemy. Even church bells were silenced, to reduce the risk of churches being targeted during air raids.

Although many people found these restrictions difficult, most accepted them as necessary for the war effort. Some felt their personal freedoms were being taken away, but others saw it as part of their duty to support the country in a time of crisis.