The 18th and 19th centuries transformed Kirklees. Quiet farming villages became crowded mill towns: Huddersfield, Batley and Dewsbury filled with factories, smoke, and workers. Working-class families were most affected, often living in one-room cottages and drinking polluted water from the rivers that powered the mills. Health suffered badly as a result of overcrowding, poor sanitation, and industrial pollution.

With little provision for waste collection, streets were littered with dung, ashes, and rubbish, while open streams carried human waste toward the rivers. Contaminated water supplies, combined with scavengers like rats and ravens, created perfect conditions for disease. However, Huddersfield avoided the extreme outbreaks seen in Leeds and Manchester, likely because it was smaller, less crowded and had fewer large factories, meaning diseases spread more slowly. Even so, illnesses such as smallpox, typhoid, and cholera still affected many people living in insanitary, overcrowded yards and cellar-dwellings.

Medical practice was gradually becoming more scientific, but it was only by tackling the root causes, clean water, drains, and better housing, that public health improved later in the 19th century.

Cholera

In 1832, cholera swept through Huddersfield. People did not yet understand germs, but they noticed that the disease followed contaminated water. Fear and panic led to the creation of local health boards and public waterworks. New laws allowed towns to build sewers, pave streets, and collect waste.

Benjamin Lockwood

Benjamin Lockwood began his medical training at just fifteen, which was normal for the time. Like most medical students of his era, he learned through practical experience: assisting established doctors, mixing medicines, visiting patients, and sometimes helping with surgery. Apprentices often travelled long distances on horseback to reach sick patients in rural villages.

After completing his apprenticeship, Lockwood established a practice in Brockholes, near Holmfirth, delivering babies, setting broken bones, and treating infectious diseases such as cholera and smallpox. Doctors of the time carried portable medical chests filled with leeches, lancets, and herbal remedies, relying on observation and experience as much as theory.

Surgery in the early 1800s was especially dangerous. There were no anaesthetics until the late 1840s, so operations were quick, often performed in homes or small surgeries. Patients were restrained by assistants, and speed could determine survival. Infection was common, as germ theory and sterilisation were unknown. Even a small wound could become deadly.

Public Health and Dr. David Hill

Dr. David Hill, Huddersfield’s first Medical Officer of Health, led campaigns to improve housing, sanitation, and water quality. At the time, public health was a new idea, before this, the government did not see it as its responsibility to protect people’s health, and care for the sick was largely left to families, charities, or local doctors. Hill’s work demonstrated the shift from reactive medicine, treating illness after it appeared, to preventative public health, aiming to stop disease before it spread.

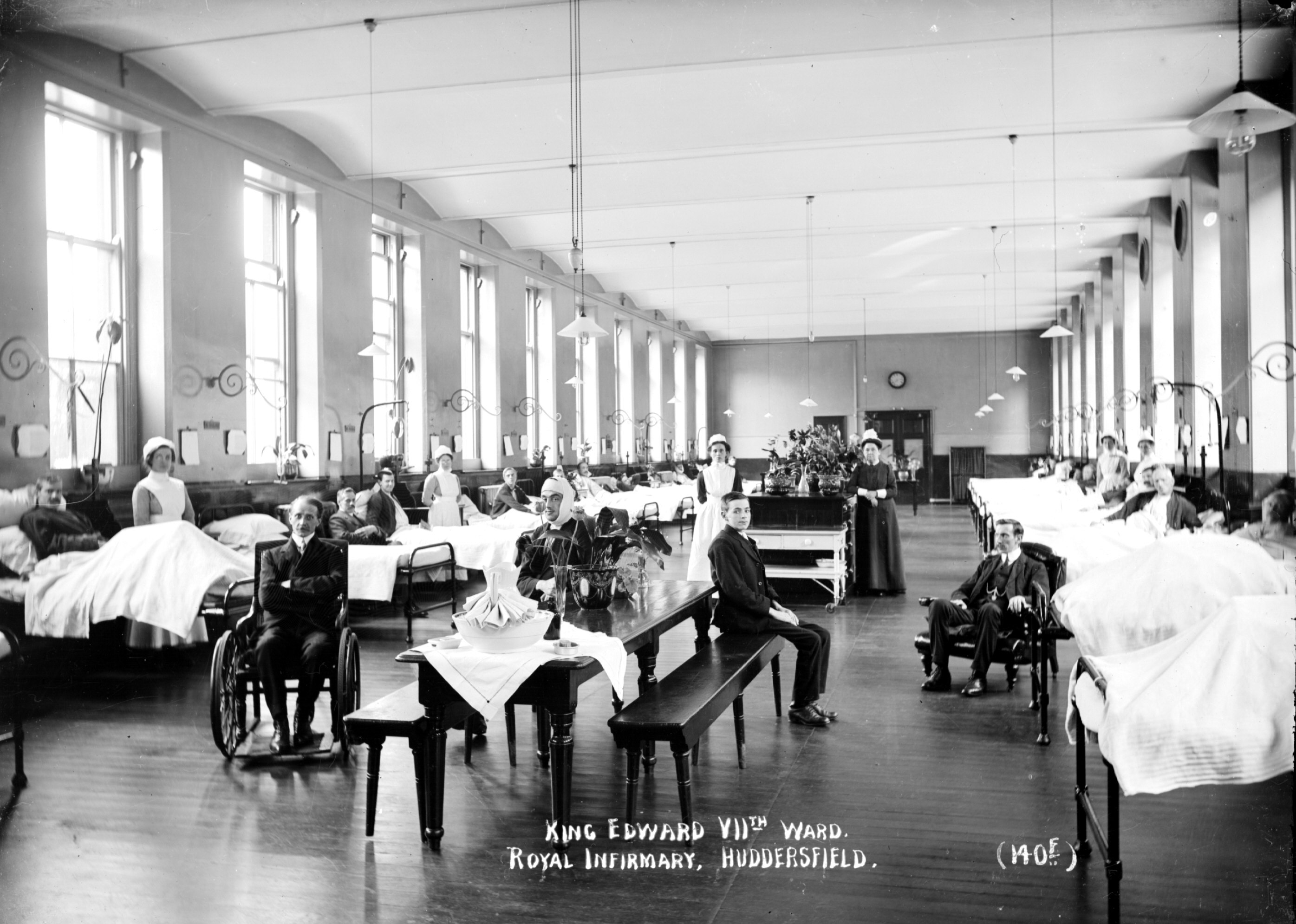

Royal Infirmary, Huddersfield

Huddersfield’s first infirmary opened in 1831, funded by donations from both factory owners and workers. It gave people a proper place to receive medical care, especially after accidents in the mills. The building was designed by John Oates, set in gardens, and had a grand entrance inspired by a Greek temple. Over time, it grew from 20 beds to 85 by 1885.

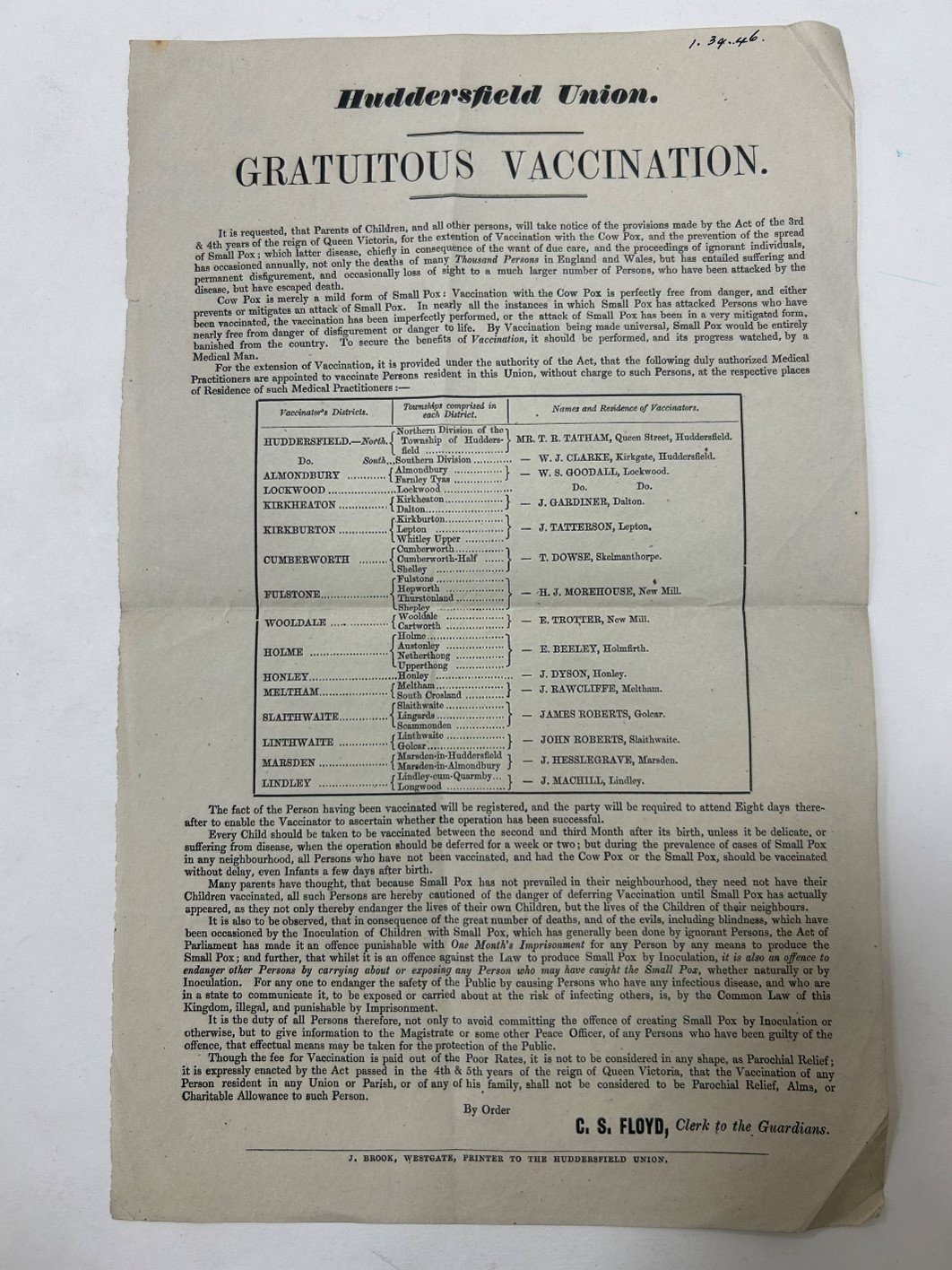

At the same time, doctors and nurses began to organise more formally, and midwives started to receive training. In 1853, smallpox vaccination became compulsory across the country, helping to prevent deadly outbreaks. Despite these improvements, life was still hard. Factory injuries, lung diseases from dust, and malnutrition were common. In Dewsbury, the workhouse infirmary cared for the poorest people, offering beds, simple remedies, and gruel.

These local changes were part of national public health reforms. Influenced by pioneers like Florence Nightingale, hospitals and nursing became more organised, cleaner, and safer. Her work helped improve hospital hygiene, reduce infections, and train nurses properly, changing how people were cared for all over Britain.