By the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066, small farming settlements in the valleys around Dewsbury, Batley, and Huddersfield had local priests and healers who helped the sick. Parish churches often acted as places of care, offering prayers or herbal remedies to those who could not afford a professional healer.

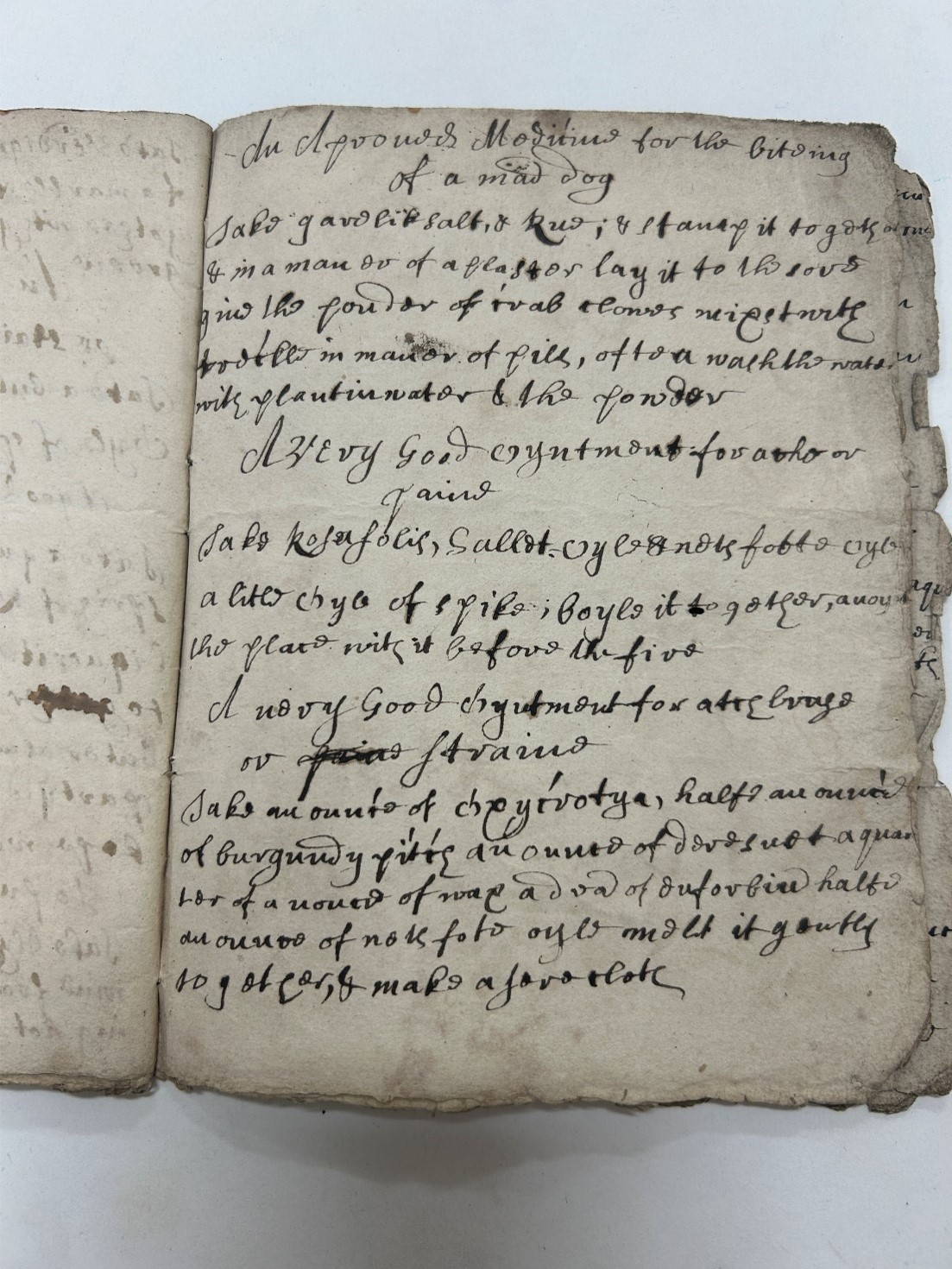

Many treatments relied on plants and natural ingredients, such as mint for stomach pains, willow bark for fevers, and garlic or honey to fight infection.

Wise women and early apothecaries prepared these mixtures, passing knowledge down through families and local tradition. Herbs were often grown in church or monastery gardens, where they were dried and stored for use in these simple medicines.

These local healers were very important for community healthcare, especially for people who could not afford trained doctors. Over time, however, their knowledge was often dismissed or ignored as medicine became more professionalised and male dominated. Despite this, their remedies and skills remained a vital part of healthcare for centuries.

This tradition of herbal remedies continued for centuries and lasted all the way to the nineteenth century, when apothecaries gradually became chemists.

Religion was the main explanation for disease. Illness was often seen as punishment from God or the work of evil spirits. However, some healers also followed ancient medical theories, such as the four humours (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) - believing that keeping these in balance was the key to good health.

Life expectancy was short, and survival often depended on family support, faith, and the skills of local healers.

Monasteries and Care

In medieval Kirklees, caring for the sick was mainly the responsibility of the Church. Kirklees Priory, founded in the 1100s, had a small infirmary where nuns looked after travellers, the poor and the sick. Patients could expect rest, simple food, warmth, and basic herbal remedies, rather than cures for serious illnesses, so the infirmary was more a place to recover strength and be cared for than to fully recover from disease. The nuns grew healing herbs such as mint, sage, and rue and used them to make simple medicines. Often, this was the only help available, as hospitals like those we know today did not exist.

During the 16th century, healthcare and education was entirely dependent on charity. Care for the poor and sick often depended on local benefactors who gave money or land to support schools, alms-houses, and basic medical aid.

Black Death

Arriving in England in 1348, the Black Death spread through towns and villages of the West Riding, including areas now in Kirklees. Symptoms included high fevers, painful swellings, and death within days. Entire families in the Spen and Colne Valleys were wiped out, leaving villages half-empty.

People believed the disease was caused by bad air or divine punishment, not fleas and rats. Bells were rung to warn of infection, and herbs were hung or burned to purify the air.

Without hospitals, the sick were isolated in pesthouses on the edges of towns. Later outbreaks continued, such as 111 deaths in Birstall (1587–88) and 130 in Mirfield (1631). Victims were buried quickly in pits at Snakehill, Littlemoor, and Eastthorpe Lane. The plague returned for centuries, leaving lasting marks on Kirklees’s people and landscape.

Women and Health Care

Estate records, such as those from Oakwell Hall, provide a rare glimpse into the work of women involved in healthcare during this period.

Midwives were central to medical care in this period, often called upon for urgent journeys to deliver babies or assist with complications. For example, Oakwell Hall’s steward, John Matteson, recorded a trip to fetch a midwife ‘in haste’ on 4th December 1610. On 20th December he ‘carried the mydwif home’ after baby Abigail Waterhouse’s birth.

Midwives not only helped deliver babies, but also advised on herbal remedies, assisted the sick and cared for mothers and infants when formal medical services were unavailable. Before hospitals existed, midwives were vital healthcare providers, passing down knowledge through apprenticeship and experience. Their work was very informal and usually not well paid, but it was essential for families and communities.

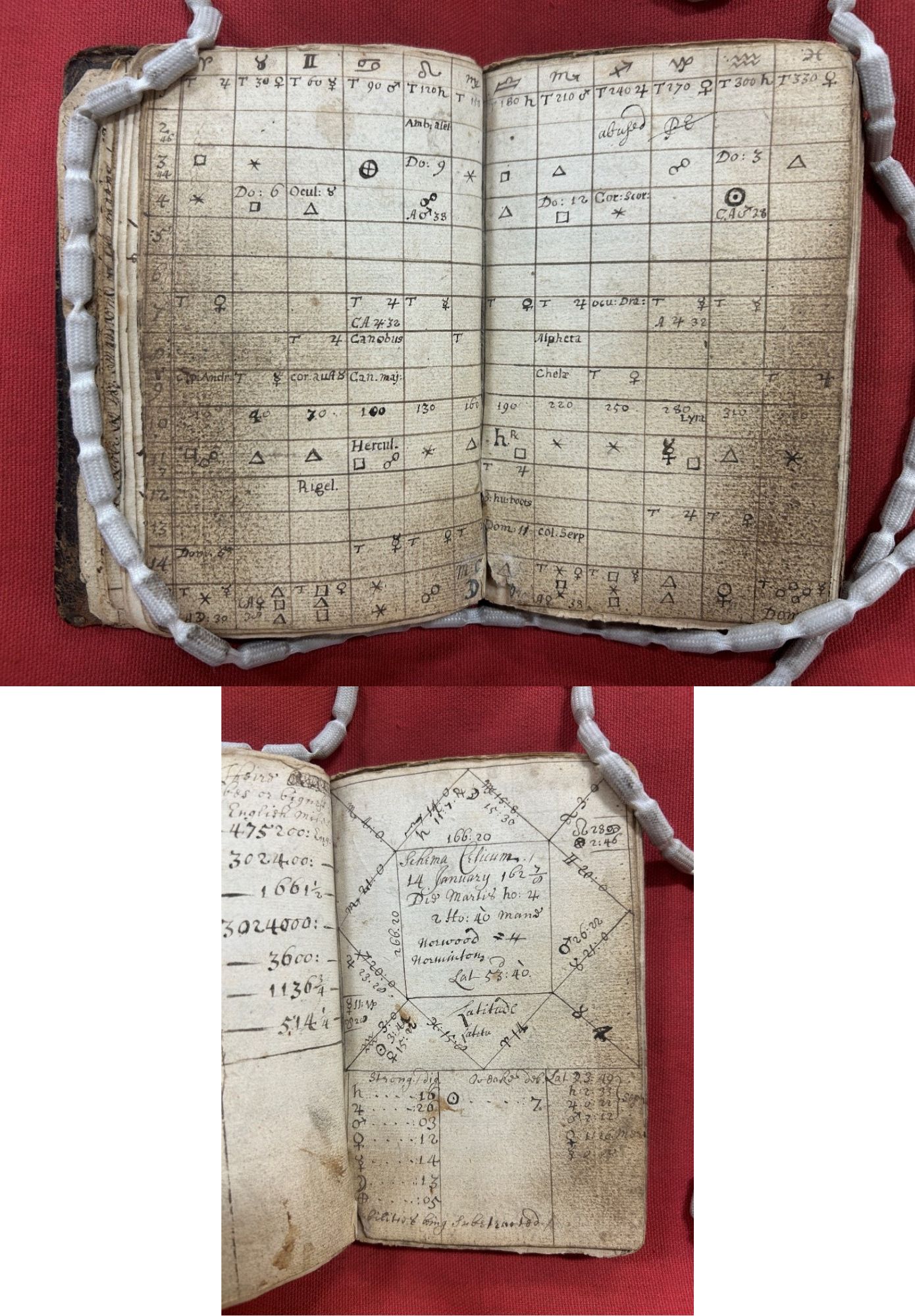

Astrology

In the 1600s, medicine and astrology were closely linked. Many healers believed that the stars and planets could influence a person’s health, personality, and even their fate. Famous astrologer-physicians like Simon Forman and Richard Napier kept detailed records of their patients, drawing astrological charts to guide their treatments. They believed the position of the planets affected the body’s balance and could help explain illness.

Astrology was used not only in London but across England, including in Kirklees. Records show that Mrs Anne Kay (Neville) of Woodsome Hall, near Farnley Tyas in Almondbury, consulted astrologers nine times in the early 1600s. In 1623, her case was recorded as a “disease of the mind,” showing how people sought both medical and celestial advice for physical and emotional troubles.

Similarly, Richard Armitage’s notebook from 1664 shows the use of astrological tables in diagnosing and treating illness.