By the early 1900s, medicine in Kirklees was changing fast. Science began to replace superstition, and people started to understand that germs, not bad air or spirits, caused disease. Local councils employed Medical Officers of Health to check food, water, and housing. New hospitals were built, including St Luke’s in Huddersfield and the Dewsbury Isolation Hospital, which treated infectious illnesses such as scarlet fever and diphtheria.

Benjamin Broadbent

In the early 1900s, Benjamin Broadbent, the Mayor of Huddersfield, became concerned about how many babies were dying before their first birthday. He wanted to make sure every child had a healthier start in life. In 1905, he introduced several new ideas to help families. Parents had to register births early so that health officials could visit quickly. Female health visitors were appointed to visit mothers at home and offer advice about feeding and hygiene. A day nursery opened for working mothers, and a milk depot was created to provide clean, safe milk for babies.

Broadbent also made a personal promise to give one pound to every baby born in the Longwood area during his year as mayor (around £100 in today’s value), once they reached their first birthday. When each baby was born, parents received a promissory note printed with advice about caring for infants. This information was written with help from Dr Moore, a local doctor. Broadbent’s ideas helped make Huddersfield one of the first towns in the country to take responsibility for the health of mothers and babies.

World War One

The First World War brought huge changes to medicine and healthcare. Many soldiers returned home with serious injuries, so new hospitals were needed. In Huddersfield, a large military hospital opened at Royds Hall in 1915. By 1917, there were nineteen smaller hospitals in local buildings such as churches, chapels, and schools. Together, they provided more than 2,000 beds and cared for thousands of wounded soldiers.

Many local women volunteered as nurses or assistants through the Voluntary Aid Detachment. Their hard work and courage helped to change people’s attitudes towards nursing, and the experience gained during the war helped to shape modern medical care in Britain.

The First World War changed medical care for individual people as well as entire communities. New treatments and technologies, including X-rays, plastic surgery, blood transfusions, and improved surgical techniques, helped doctors save lives and repair injuries that would previously have been fatal or permanently disabling.

Childhood diseases

By the 1950s, life in Kirklees was improving, but diseases still posed a serious threat to children’s health. Smallpox, a deadly and contagious illness, continued to cause outbreaks even though a vaccine had been discovered more than a hundred years earlier. When smallpox returned to parts of Yorkshire in 1949, health workers launched mass vaccination campaigns to protect families. These efforts showed how much public health had changed since the 1800s, now the government and doctors worked together to prevent disease, not just treat it.

Other childhood illnesses, such as measles, diphtheria, and whooping cough, were also common. The introduction of the diphtheria vaccine in the 1940s helped save many young lives, and by 1950 the number of cases had fallen sharply across the country.

Entry from December 22nd 1944: “The school closed for the Christmas holidays. The attendance for the past few weeks have been very poor owning to an outbreak of whooping cough, mumps and measles”

Credit: West Yorkshire Archive Service [WYK1927/3] Log Book of the Batley Carr Council Infants’ School.

In the 1950s, another new threat appeared: polio, a virus that could cause paralysis. Local doctors and nurses in Huddersfield and Dewsbury helped deliver the first polio vaccinations. Families were encouraged to bring their children to clinics for the free injections.

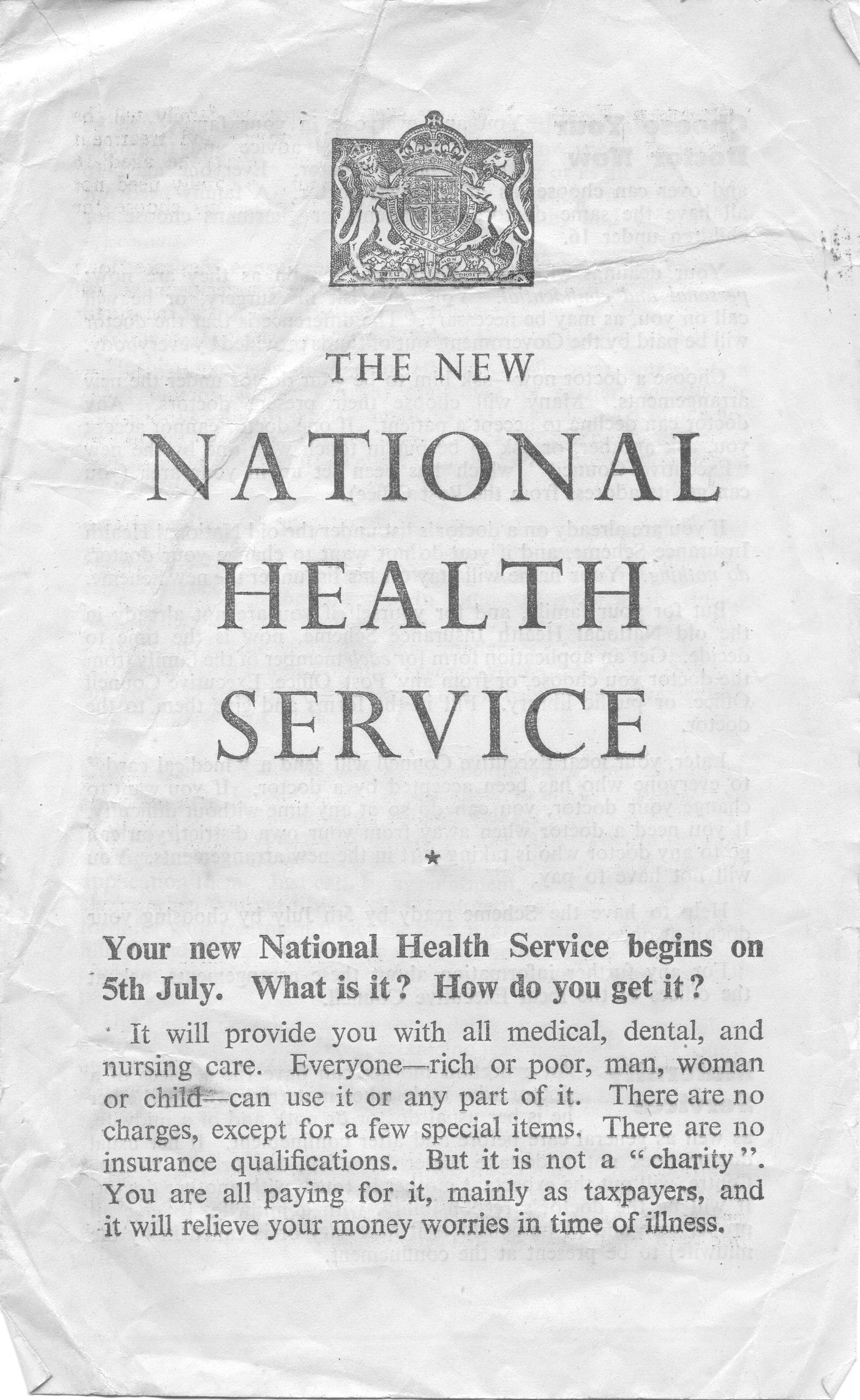

These clinics were part of the new National Health Service (NHS), which was set up in 1948 to provide free healthcare for everyone in the UK, making it easier for all children to be vaccinated and cared for.

Daphne Steele

Daphne Steele was a remarkable nurse who made history in the 1960s. Born in Guyana, she trained as a nurse and midwife and came to Britain to work in the NHS. She became Britain’s first Black matron, leading the team at St. Winifred’s Hospital in Ilkley, not far from Kirklees. This was an exceptional achievement, because Black nurses often faced unfair treatment. Some were paid less than other nurses, were not offered promotions and were treated unfairly because of the colour of their skin.

Daphne’s story shows how the NHS brought together people from all over the world to care for local communities. Nurses like her helped shape modern healthcare, combining skill, compassion, and determination to make sure everyone received proper treatment, no matter their background.

Today, her legacy is remembered locally, with a building at the University of Huddersfield being named after Daphne Steele to celebrate her pioneering work.