The Industrial Revolution brought about dramatic changes in industry and made huge changes to people’s lives. Some benefitted, but others, especially children and workers, felt great hardship. People began campaigning to improve the conditions of working people.

Luddites

The Luddite movement was a significant part of the industrial history of Kirklees and the wider region. Beginning in Manchester in 1779, it was led by skilled textile workers who opposed the introduction of machinery that threatened their jobs and way of life. The movement spread to Nottingham in 1811 and reached Yorkshire in 1812.

The Luddites in West Yorkshire were mainly hand croppers—highly skilled workers who trimmed the surface of cloth using large shears. Their work was well-paid, but the invention of mechanised shearing frames meant one machine could replace ten men, causing widespread job losses. George Mellor led the Marsden Luddites in their campaign against this change. Throughout the first half of 1812, mills across Huddersfield and Kirklees were targeted in Luddite attacks, as workers fought to defend their livelihoods from industrial change.

In February 1812, Luddites attacked wagons carrying machinery to Rawfolds Mill in Cleckheaton. The conflict escalated with a major attack on the mill in Liversedge on 11 April 1812, where two Luddites were killed, and later that month the mill-owner William Horsfall was murdered. These events triggered a severe government crackdown.

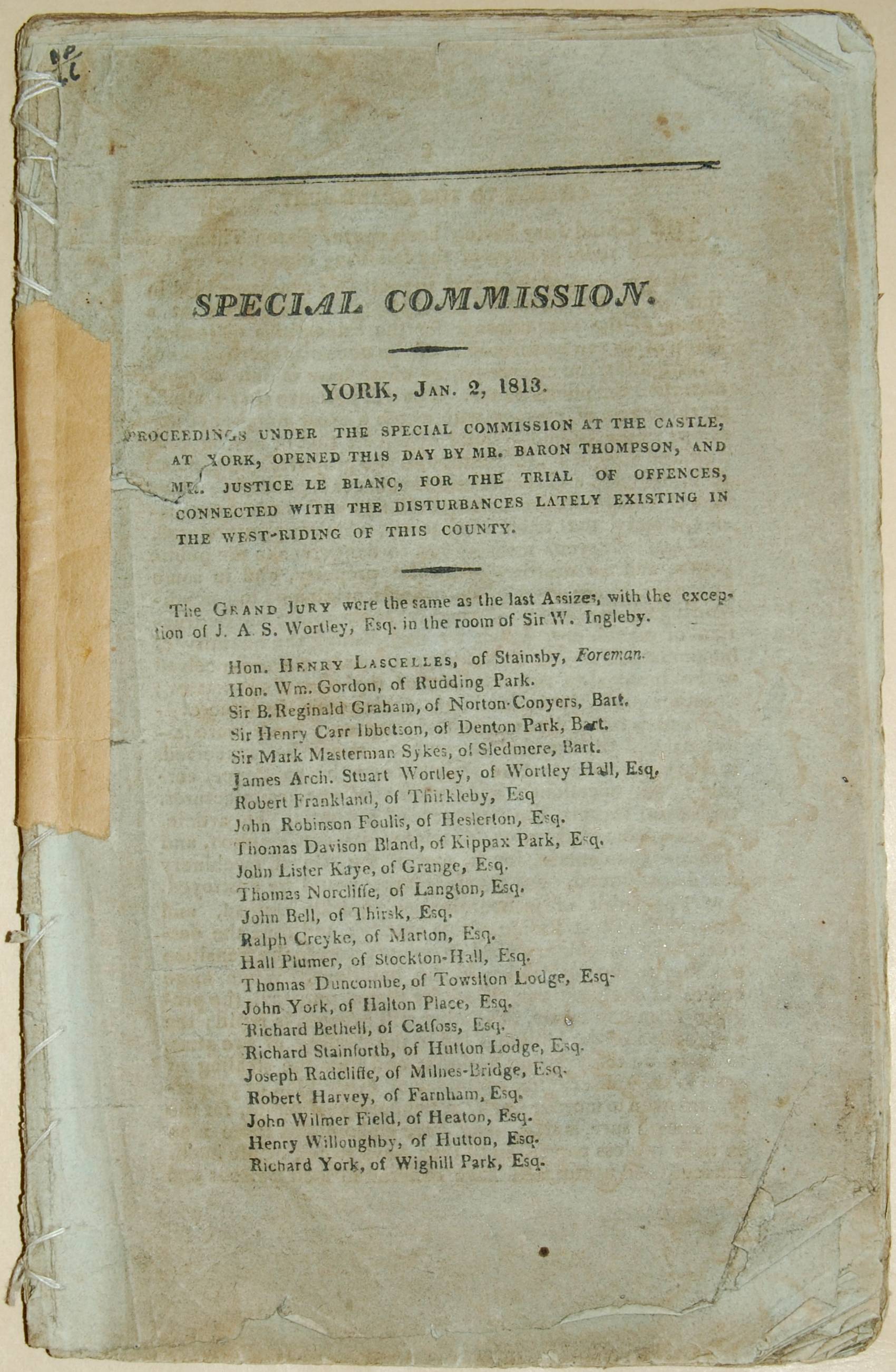

In January 1813, seventeen men were hanged in York for their involvement. Public opinion was divided at the time, some people saw the Luddites as dangerous criminals, while others sympathised with their struggle to protect jobs and traditions. Hanging was not unusual in those days, as it was a common punishment for serious crimes, but executing so many at once sent a very strong message from the authorities.

To suppress the movement, the authorities appointed Huddersfield magistrate Joseph Radcliffe, who used troops to restore control. Through mass arrests, harsh punishments, and the execution of key figures, the government successfully crushed the Luddite uprising by the end of 1813, bringing an end to large-scale organised resistance in the region.

Democracy and the Skelmanthorpe Flag

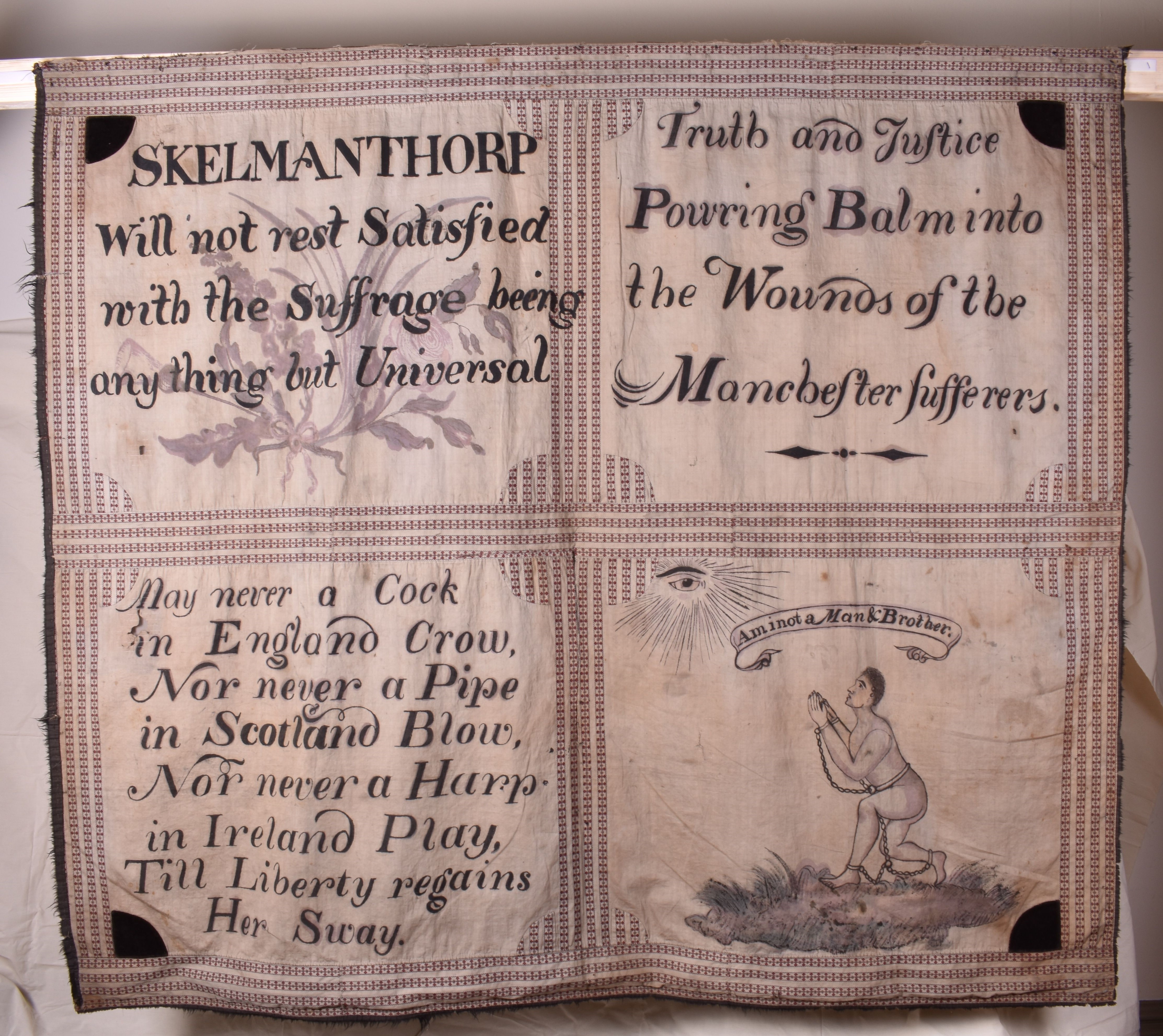

The Skelmanthorpe Flag, created in 1819 by local designer Mr Bird, is a powerful symbol of protest and political activism in Kirklees during the 19th century. Made up of four panels, the flag called for universal suffrage, votes for all men, and highlighted major social and political injustices of the time.

Each panel represented a cause. The first called for voting rights for all men (but not women at that time). The second demanded justice after the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester in 1819, when peaceful protesters for democracy were killed by soldiers. The third opposed slavery, and the final panel made a broad appeal for justice and liberty for everyone. Banners like this were carried on marches and displayed at meetings to show what ordinary people were fighting for.

The flag was carried at large public demonstrations, including a mass meeting at Almondbury Bank in November 1819 attended by 40,000 people. Fearing unrest, the authorities responded with force. To protect the flag from being seized or destroyed by government agents, it was hidden—likely buried—and remained out of sight for many years.

The Skelmanthorpe Flag remains a powerful reminder of the area's long tradition of protest and the fight for rights and representation.

Richard Oastler

Richard Oastler was a passionate campaigner for workers’ rights, especially for children working in textile mills. Born in Leeds, he later moved to Huddersfield as the landlord of the Fixby estate. There, he witnessed the harsh conditions faced by children—many worked up to 14 hours a day in noisy, dangerous factories.

Outraged by what he saw, Oastler called this exploitation "Yorkshire Slavery" and dedicated his life to fighting it. In 1836, he even encouraged workers to sabotage factory machinery in protest. His outspoken activism made him a well-known and controversial figure.

“At one of these mills… one boy about ten or eleven years of age, has worked for five months from SIX o’clock in the morning to TEN o’clock at night - say FOURTEEN hours per day, allowing TWO hours for meals. This boy has very frequently been sick and ill, when he has been kept to his labour; nine days ago, however, he was obliged to be laid up, and has not yet returned to his work. About FORTY boys have worked along with him. Now the master of this mill is a strenuous petitioner against ‘[omitted] Slavery’ and at the same time a practiser of, and petitioner for, ‘Yorkshire Slavery’” - ‘Slavery in Yorkshire’ (October 30th 1831) A letter from Richard Oastler in the Leeds Intelligencer.

In 1840, Oastler was imprisoned for debt, but he continued to write about politics and social reform from his cell, publishing his views in a series called the Fleet Papers. He earned widespread support among the working class and became known in Huddersfield as the Factory King for championing the rights of children and labourers.

Oastler's efforts helped bring about significant reforms. Early laws reduced children’s working hours to 12 per day, and in 1847, the Ten Hour Act was passed. This law limited children’s workdays to 10 hours, required 2 hours of schooling, and banned night work for young workers—laying the groundwork for future improvements in workers’ rights.