When the Industrial Revolution began, life changed quickly for weavers and their families. Before this time, people used hand-operated machines like spinning jennies and looms in their own homes to make cloth. But soon, new machines were invented that were much bigger and faster.

These large machines were too big to fit inside cottages, so weaving and spinning moved from people’s homes to big buildings called mills. At first, only some of the cloth-making steps happened in mills. But by the 1860s, huge woollen mills powered by steam were built. These mills could carry out all the stages of making cloth in one place – from washing the wool (scouring) to carding, spinning, weaving, dyeing, and finishing it.

Many mills were built with several floors so that different jobs could be done on different levels of the building; these were known as vertical mills. (Inside, the upper floors often held spinning frames, while lower floors housed weaving or finishing, all powered by a central waterwheel or steam engine.)

Work opportunities tripled in number between 1750 and 1800, and by about 1820 more than 50% of the textile workers were women. This line of occupation was seen as a good way of making a living despite the low pay. A working day consisted of 12 to 14 hours with many mills being unhealthy and dangerous places to work. Since the workers required no special qualifications, it was entirely possible for children to do the same work as women, and indeed many did so in the Yorkshire textile industries. Their powerlessness was enforced in several ways: they could be sacked or blacklisted for speaking up, denied access to company housing, or threatened with the workhouse if they could not support themselves.

In 1824, Joseph Armitage of Highroy built the first mill in Honley, starting the Industrial Revolution in this area. Soon, more mills appeared across Kirklees, and by 1849 almost everyone in Huddersfield and the surrounding districts (around 108,000 people) worked in the wool industry. There were a few cotton and silk factories, but these were rare. Many families were very poor, partly because mill owners paid very low wages and controlled housing and working conditions. The cycle of poverty made it hard for families to escape these conditions: children missed out on school, parents could not earn enough to improve their lives, and if families fell behind, they risked being sent to harsh workhouses. At the time, the government did very little to protect workers, which meant poor families had few ways to improve their situation and were trapped in poverty for generations.

Children often had to work in the mills to help their families survive. In mills with spinning mules, they worked as ‘piecers’, leaning over machinery to tie broken threads, or as ‘scavengers’, crawling under machines while they were still running.

By 1830 reformers, like Huddersfield’s Richard Oastler, made the government aware of the conditions in the mills, where children as young as five often worked. As a result, a Royal Commission was set up to investigate the problems, the Select Committee collected evidence from witnesses who had firsthand experience of conditions in the factories.

“I reside at Northgate, Huddersfield, in Yorkshire,- I was 17 years of age, on the 21st of April. My father died six years ago, but my mother is still living. I began to work when seven years old at George Addison’s, Bradley Mill, near Huddersfield. The employment was worsted spinning; the hours of labour at that mill were from five in the morning till eight at night, with an interval for rest and refreshment of thirty minutes, at noon; there was no time for rest or refreshment in the afternoon; we had to eat our meals as we could, standing or otherwise. I had fourteen-and-a-half hours actual labour when seven years of age and I received as wages two shillings and sixpence per week. I attended to what are called ‘throstle machines;’ this I did for two and a half years, and then I went to the steam looms for about six months.” Evidence given to the Select Committee (1832) from Bradley Mill worker Joseph Habergam.

“The children are generally cruelly treated; so cruelly treated, that they dare not hardly for their lives be too late at their work in a morning… It is a very difficult thing to go into a mill in the latter part of the day, particularly in winter, and not to hear some of the children crying for being beaten for this very fault (for not being able to work very well when they are very tired). How they are beaten depends upon the humanity of the hubber or billy-spinner; some have been beaten so violently that they have lost their lives in consequence; and even a young woman had the end of a billy- roller jammed through her cheek. The billy-roller is a heavy rod from two to three yards long; and of two inches in diameter, and with an iron pivot at each end; it runs on the tops of the cordings over the feeding cloth.” Evidence given to the Select Committee (1832) from Scholes clothier Abraham Whitehead.

Bottom Bank Upper and Lower Mills, Almondbury

Bank Bottom Mill (later known as Marsden Mill), established in 1824 in Marsden, West Yorkshire, was an important centre for woollen cloth production during the Industrial Revolution. The mill was operated by Norris, Sykes and Fisher, a local firm that employed many workers, including children.

In 1834, Norris, Sykes and Fisher's mill was visited by the Royal Commission on the Employment of Children in Factories, which was investigating working conditions for children. The commissioners found that boys and girls under the age of ten were employed at the mill, earning just 3 shillings a week (around £21 in today’s money), roughly half the pay of an adult. The standard working week was 69.5 hours, with time off only on Sundays, Christmas Day, Good Friday, and a few other half-days in the year.

The Commission’s report exposed the widespread use of child labour in mills like Bank Bottom, drawing attention to the long hours, low pay, and dangerous conditions young workers faced. These findings helped to raise public concern and led to important legal reforms, including early Factory Acts that began to limit children's working hours and improve their conditions.

"We are of the opinion that any legislative interference will prove prejudicial to both masters and workmen, more especially so where only water power is used. There exists no necessity whatever in the mills employed in manufacturing woollen cloths, and did we deem it needful to legislate on the subject, so difficult is the business, we should feel ourselves utterly at a loss how to act." From Supplementary Report of the Central Board of Her Majesty's Commissioners Appointed to Collect Information in the Manufacturing, as to the Employment of Children in Factories, and as to the Propriety and Means of Curtailing their Labour (1834) Factories Inquiry Commission.

The 1844 Factory Act was an important law aimed at improving conditions for children working in factories. It set a minimum working age of nine, required employers to keep age certificates for child workers, and limited their working hours: children aged 9 to 13 could work no more than nine hours a day, while those aged 13 to 18 could work up to twelve hours. The act also banned night work for children and required them to attend school for two hours each day.

At school, children learned basic reading, writing, and arithmetic, and sometimes religious lessons or simple vocational skills to help them in future jobs. To enforce the law, four factory inspectors were appointed. This act was a key step in the growing efforts to protect young workers during the Industrial Revolution.

Disasters

On the 14th of February 1818, a terrible fire broke out at Colne Bridge Mill, a cotton factory near Huddersfield. The owner of the mill was Thomas Atkinson, who also owned the Bradley Mills in Huddersfield. The fire started very early in the morning, around 5 o’clock, while many workers were still inside.

“On the morning of January 14th 1818, a calamitous fire occurred at the above mill, and no fewer than seventeen females between the ages of nine and eighteen years, perished in the flames… At the inquest, it was shown that the iniquitous system of working children in the night time, when their employers were in bed, prevailed at this mill and that it was customary to lock the children in. To this latter cause was due the lamentable loss of life which occurred. The overseer also was not overkind. I was informed by Sarah Moody, now the wife of William Wood, who resided at the top of Heaton Moor, about two years ago, that she was with her two sisters in the mill, and that it was she who when kneeling cleaning the machinery, first saw the flames through the chinks in the mill floor, and gave the alarm to the overseer, James Sugden. That she was accompanied by her ‘mate’ or companion when she gave the alarm, and that the overseer when informed of the fact was very wroth, and threatened to punish them if they did not return to their work. She however refused to return, but her companion did, and was numbered with the dead. Sarah Moody was between ten and eleven years of age at the time, and she alleges, that that she heard Mr Atkinson upbraid the overseer in the yard in the forenoon of the day of the fire, for not having looked after the hands instead of the bales of cotton. It is generally believed by those of our townsmen who were living at the time, that the keys had been misplaced and were not forthcoming when wanted; hence the serious loss of life.” From History of the Factory Movement. (1888) Croft, W. R.

At the time, it was common for children to work long hours, even at night. That night, 17 girls aged between 9 and 18 were working in the mill. Sadly, when the fire began, they were trapped inside and could not escape. All of them were killed. The fire started when a young boy was sent to a room in the mill called the carding room. He carried a candle to see where he was going, but it accidentally set fire to some nearby materials. The flames quickly spread through the building, and there was no way out for the girls.

The disaster at Thomas Atkinson’s cotton mill shocked many people. It showed just how dangerous mill work could be, especially for children. This tragedy helped raise awareness about the need for better safety in factories and stronger laws to protect children at work.

Bring aart yer ghosts! Yo dark, grey mills;

Wistful an' watchful, wi calm, grave een.

Holdin' dumb ghost-shows, where t'stark leet spills

Tremblin' dubs, where t'dayleet's never seen.

Bring aart yer ghosts! Do shadders shed tears?

Poor, locked-up childer, O motherin' years.

Martyrs wer' burnt; — but they had a cause —

Yo hed nowt, but clammin', and t'tawse.

A young lad whistled as he loaded a scray;

A ghoast-child smiled as it donced away.

A neon lamp flickered, then flooided wi' leet;

A throng o'wraiths trailed aart into t'neet.

‘T’Shadder Show’ (1950s) by Fred Brown, a poem written about the tragedy.

Dye industry

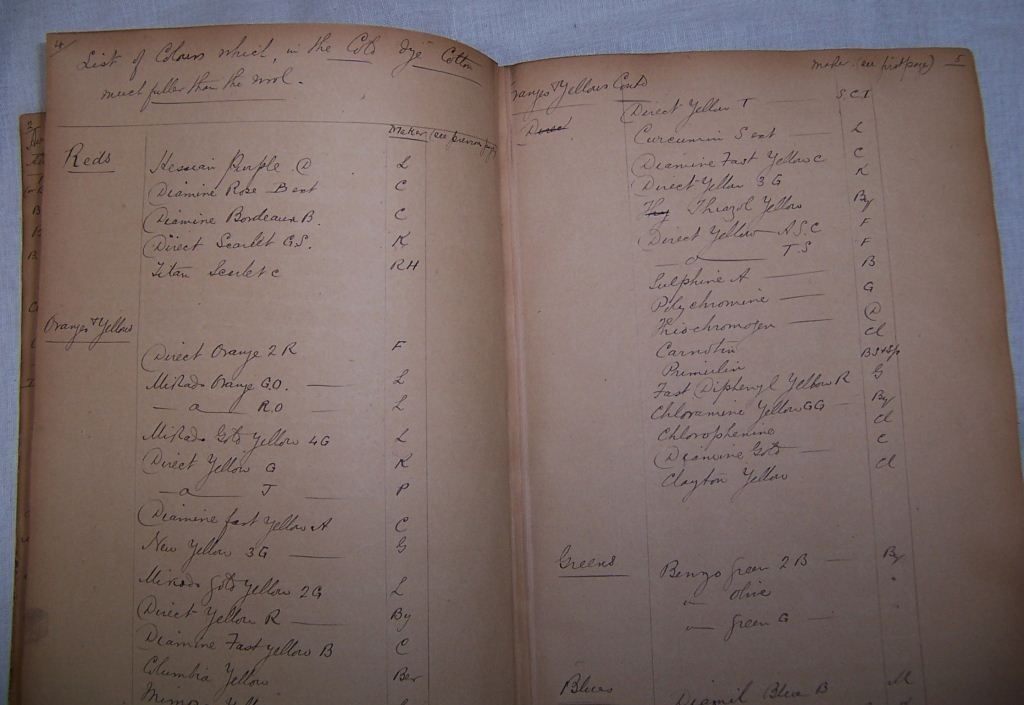

During the Industrial Revolution, the booming textile industry in Kirklees created a growing demand for dyes, bleaches, and other chemicals used to treat and finish cloth. Early in the 19th century, dyes were mainly made from plants, and little was understood about their chemical structure until scientists began analysing them in the mid-1800s. This led to the development of synthetic dyes, which revolutionised the industry.

Kirklees became a centre for chemical innovation, with bleach works and small dyeworks forming the foundation of a new chemical sector. One key figure was Read Holliday, who began producing ammonia in Huddersfield in 1830. By 1860, he expanded into synthetic dye production, starting with magenta and later offering a range of colours including red, violet, and blue. His company was awarded numerous patents, and in 1880, Holliday’s sons developed a groundbreaking azoic dyeing process that would shape modern dyeing and printing methods.

Local dyeworks also played an important role, such as the Moll Spring Mills and Dye Works near Honley, operated by silk dyer George William Oldham and his brother. These sites were essential to the region’s textile and chemical industries, though not without risks—such as a major fire in 1866 caused by flammable materials near a stove.

This story of innovation and industrial growth helps illustrate how Kirklees contributed to major advances in dyeing and chemical manufacturing during the Industrial Revolution.

Shoddy and Mungo

The textile industry in Kirklees was not only known for producing new fabrics but also for pioneering one of the earliest examples of recycling. In 1813, Benjamin Law of Batley developed the shoddy and mungo process, which involved shredding old woollen rags and industry waste to make new yarn. This was especially useful for creating blankets and uniforms for soldiers. For over 100 years, the Batley and Dewsbury area became a global leader in this innovative method.

Sorting and processing the rags was tough, unpleasant, and hazardous work. The rags were often dirty, smelly, and infested with fleas. Workers had to clean and scour them, sort by type, colour, and quality, then grind them using machines. The wool was then “willeyed” to fluff and lighten it before undergoing regular textile processes like spinning and carding.

“Women, with their squalid, dust-strewn garnments, powdered to a dull greyish hue, and with their bandages tied over the greater part of their faces, moved like reanimated mummies in their swatchings; I had seldom seen anything more ghastly” - Angus Bethune Reach (1849)

The work came with serious health risks. The dust from grinding caused respiratory problems known locally as Shoddy Fever (bronchitis), and the constant contact with filthy materials posed further hygiene issues. Fires were another major danger—machines could overheat, and the oily rags sometimes combusted spontaneously.

Despite these challenges, the shoddy and mungo industry was a vital part of the local economy and a forerunner of modern textile recycling.