Suffrage means the right to vote in political elections. In the 1800s, only a small number of men in Britain were allowed to vote. The 1832 Reform Act had extended the voting rights to all males who owned or rented property of a certain value (£10 a year – which is around £970 today). However, this only benefitted 1 in 7 men: those who were middle class. Working class men, and all women, were still excluded from the voting system.

This led to growing demands for political reform. The Chartist movement, starting in 1837, called for universal male suffrage, meaning all men should be allowed to vote, regardless of property or income. They used symbols like the Skelmanthorpe Flag during protests and meetings to push for change.

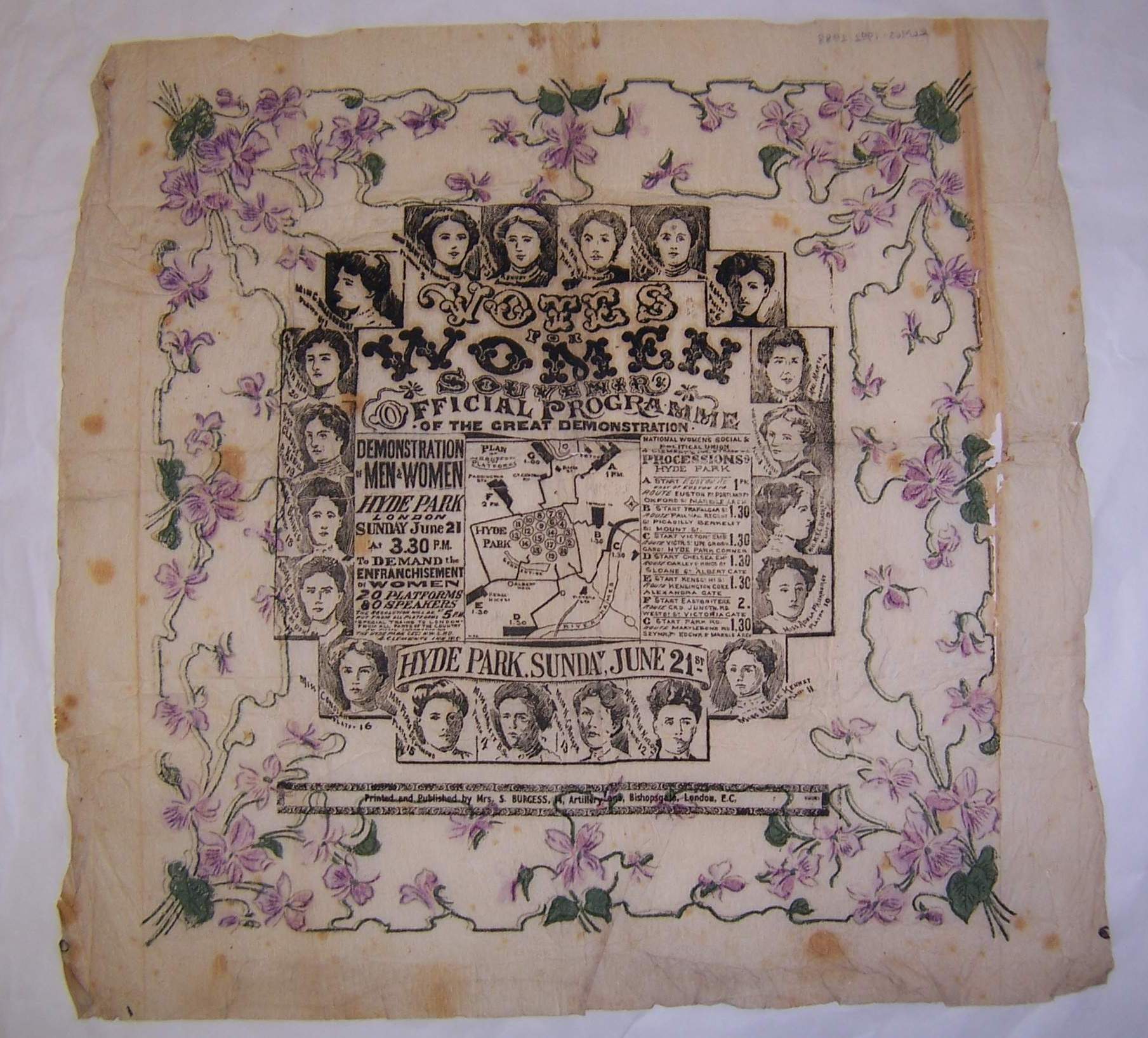

By the mid-1800s, women also began to campaign for the vote. In 1866, a petition signed by nearly 1,500 women was presented to Parliament, marking the start of a more organized women’s suffrage movement. Groups formed across the country, and women campaigned for the right to vote so they could help shape laws affecting their lives.

There were different views among suffragists. Some believed women were different from men but not inferior, with their role as homemakers, caring for the family and managing the household, being just as important as men’s work outside the home. Others argued that men and women were simply equal and should be treated the same. Both believed that having the vote would bring positive change.

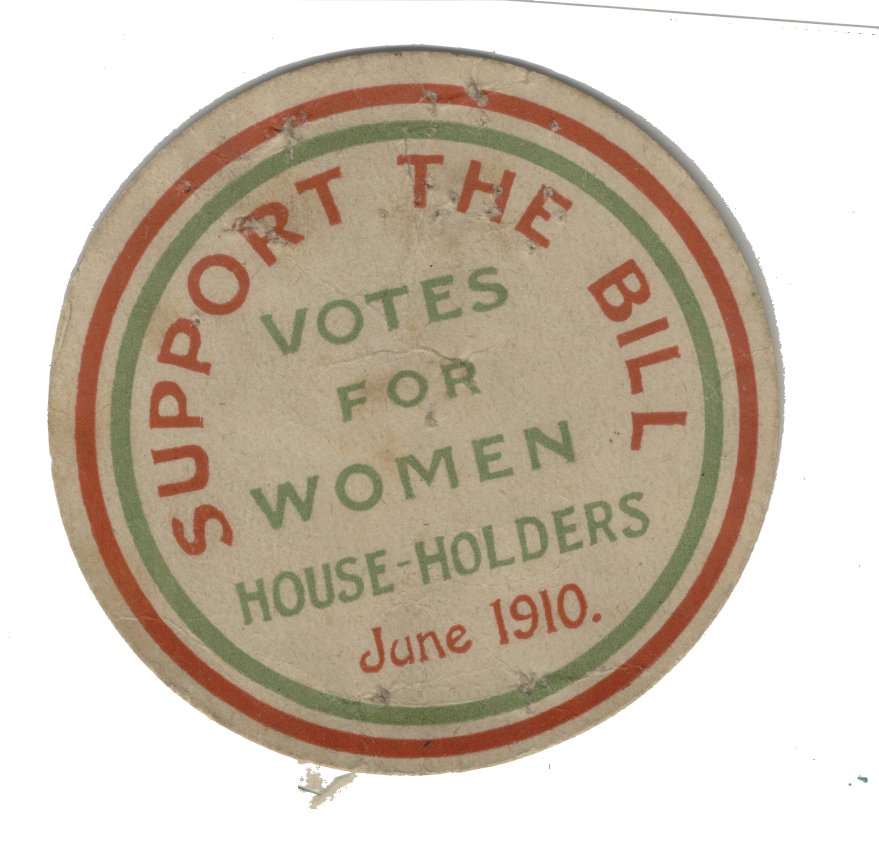

However, not everyone supported women’s suffrage. Some men, and even some women, opposed it. In 1908, the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League was formed and later joined with a men’s group. By 1914, this anti-suffrage movement had 42,000 members.

Batley and Dewsbury

In the 1870s, women in the industrial towns of Batley and Dewsbury began coming together to talk about politics, their rights as workers, and their role in society. These early meetings were an important part of the women’s suffrage movement in West Yorkshire. The women were concerned not just about getting the vote, but also about fair treatment in the workplace. They faced lower wages than men, long working hours, and few opportunities for promotion or senior positions.

Lydia Becker, a leading suffragist and founder of the National Society for Women's Suffrage, supported women in this region. She encouraged local efforts and helped connect women in Batley, Dewsbury, and Huddersfield.

Interest in the cause grew, and women held large public meetings in Batley town centre. They also gathered in homes for smaller "cottage meetings", where they read and discussed articles from Becker’s Women’s Suffrage Journal. These meetings helped women learn more, gain confidence, and support each other.

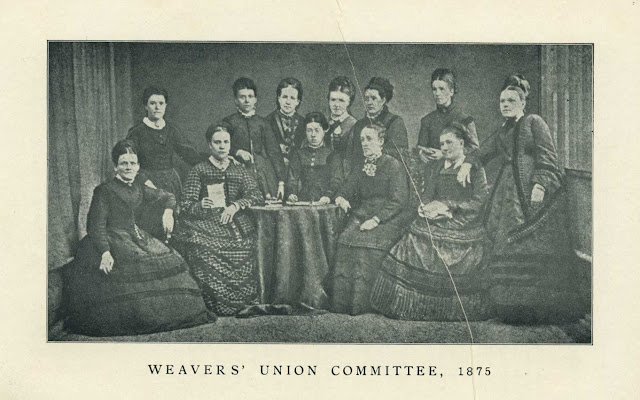

Many of the women had already gained leadership experience during the weavers’ strike of 1875, where some served on the workers’ committee. This background in trade union activism helped them become strong voices in the campaign for women’s political rights.

Batley's first major women's suffrage meeting was held on 29th February 1876 at the Town Hall. Dewsbury's newspaper, The Reporter, advertised the event:

“OUGHT WOMEN TO BE TAXED WITHOUT THE RIGHT TO VOTE FOR THOSE WHO TAX THEM? As these ladies are very clear and logical speakers, and as the question they will speak upon is one that commends itself to the lovers of fair play of all political shades, we would advise all who desire that the principles of justice should be applied to men and women alike, to attend this meeting. Several local gentlemen will also attend the meeting.” The (Dewsbury) Reporter, 26th February 1876

This newspaper article from The Dewsbury Reporter in 1876 asks whether women should have to pay taxes if they are not allowed to vote. It invites people to come and listen to women speaking at a meeting, describing them as “very clear and logical speakers.” At the time, many people did not expect women to speak in public or to be good at debating, so the newspaper’s comment shows how unusual this was. It reminds us how brave these women were for stepping into political life and speaking up for fairness.

The women’s suffrage efforts in Dewsbury and the surrounding areas received important political backing from local MP John Simon, who was a member of the Liberal Party (a political party at the time, though it no longer exists today). His support was unusual, as most male MPs did not back women’s right to vote. Simon not only supported their campaign but also agreed to present a petition to the House of Commons calling for women to be granted the vote.

Hannah Wood

Hannah Shipman was born in 1842 in Shropshire. She later moved to Dewsbury with her husband, Henry Wood, where they lived and worked in the textile industry. Hannah worked as a woollen power loom weaver, showing how women often helped support their families through factory work.

In 1875, Hannah took on a remarkable leadership role as President of the Weavers' Union Committee during a major strike in Dewsbury and Batley. This was unusual for the time, as trade unions were mostly led by men. At one key moment, around 9,000 weavers—both men and women—gathered to protest a wage cut. Hannah’s leadership and speech-making made a strong impression. This committee formed a union which joined with others to become the General Union of Textile Workers – this was the first permanent trade union in the heavy woollen section of the textile industry.

A year later, in 1876, Hannah spoke at a public women’s suffrage meeting at Batley Town Hall. Her experience as a union leader made her a confident and respected speaker. She became a strong voice for both workers’ rights and the campaign for women to gain the vote.

Hannah’s work showed how closely linked the trade union and suffrage movements were, especially for working-class women. She continued her activism until her early death from bronchitis in 1891, at the age of 49.

Ann Ellis

Ann Ellis (née Waite, 1843–1919) was a power loom weaver from Batley and a pioneering trade union leader and women’s rights activist. In 1875, she played a leading role in a landmark weavers’ strike in Dewsbury and Batley, notable for being led by women.

When mill owners attempted to cut wages, Ann helped organise a strike that drew support from both male and female workers. In a bold move, the workers elected an all-female strike committee, a historic first. Ann’s powerful speeches rallied thousands, arguing that women could not afford further hardship. Rejecting outside interference, she insisted that local working women could lead their own fight, and with solidarity from miners and fellow weavers, they won – reversing the wage cuts.

Beyond the strike, Ann opposed laws that restricted women’s work and helped set up branches of the Women’s Trade Union League across West Yorkshire. She continued campaigning for many years, but in 1885 she lost her job after speaking at a labour conference. At that time, workers had very few rights or protections, and employers could dismiss someone if they thought their political activity was causing trouble. This made it especially risky for women like Ann to speak out, even though she had managed to keep her job while challenging her employers before.

Despite her achievements, Ann Ellis died in poverty in Bradford Workhouse in 1919. Workhouses were places where people who had no money or support could live and work, but conditions were often very harsh.