Wilson Armistead was born in Leeds on 30 August 1819 and grew up in Holbeck as a Quaker. His family owned flax and mustard businesses at Water Hall, Holbeck. By the 1840s, Wilson was married with young children, running the family business and, like many Quakers, was involved in campaigning for social justice. Wilson was becoming increasingly involved in abolitionist and anti-slave ownership activity. In 1848, he published a book, A Tribute for the Negro, which is still used as a key academic abolitionist text today.

The book contains a series of biographies detailing the achievements of African people and culture. It talks of the ‘sin of slavery’ and argues against the prevailing view of the time that there was a correlation between skin colour and intelligence. A copy can be read online (see Supporting Links) or in the local history reference section of Leeds Central Library. The sentiments of equality and brotherhood are clear in the writing, but some of Wilson’s language may need contextualising for classroom activities.

In June 1850 Wilson travelled to the United States, meeting abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison. He also met Ellen and William Craft. Ellen and William were previously enslaved people who had escaped from a plantation in Macon, Georgia (in the Southern U.S) to the free North in 1848. To enable their successful escape from Georgia, Ellen (who was mixed heritage and fair) pretended to be a White enslaver travelling with her ‘slave’, William.

In 1850, the United States passed a law called the Fugitive Slave Act which required former enslaved people to return to their enslavers even if they were living in free northern states.

Ellen and William escaped to England, where they made a living speaking publicly about their experiences and abolition. At the time of the 1851 census they are staying with Wilson and his wife Mary in 38 Springfield Place, Holbeck. Wilson recorded his guests on the census as ‘fugitive slaves’ which was covered extensively in the press of the day as an unusual act of abolitionist activism.

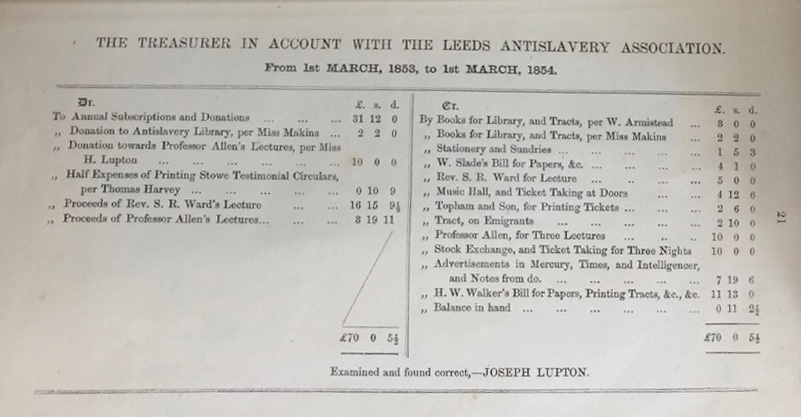

In 1853, Wilson founded the Leeds Anti-Slavery Association. Wilson was president and his wife, Mary, was the librarian.

The Leeds Anti-Slavery Association was forward thinking even for abolitionist groups of the time as it allowed women to join and campaign alongside men.

The association had dual mottos of ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’ with ‘Am I not a woman and a sister?’ This gender equality impressed Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, who was a guest speaker of the Association in 1853. Women had long campaigned for abolition of the slave trade, most probably more in their own social circles than alongside men, and had organised boycotts of sugar harvested from plantations that used the stolen labour of enslaved people.

Wilson edited a collection of abolitionist writing, Five Hundred Thousand Strokes For Freedom in 1853 and published God’s Image in Ebony in 1854. The final house he lived in was ‘Virginia Cottage’, now part of Leeds University campus, which had been built and named for a previous owner who owned plantations and enslaved people in Virginia. The African-American abolitionist William Wells Brown wrote, ‘Few English gentlemen have done more to hasten the day of the slave’s liberation than Wilson Armistead’.

Ethical note about living descendants: We don’t know whether Wilson or Mary, have living descendants, and if they do, where they are in the globe, or how they might feel about their ancestors. Whilst framing the actions of the past within the relevant time period and a modern context, we have to be ethically aware and respectful of people’s family histories.