Jacob Kramer was a painter and lithographer.

He was born in the Ukraine in 1892, the son of a court painter and an opera singer. The family fled the Russian anti-Jewish pogroms and arrived in Leeds in 1900, via Hull. Jacob’s father had a friend in photography in the city and thought he could get work through that, even if he couldn’t be a painter. The family lived in The Leylands: a slum of closely packed houses and terrible living conditions with a large proportion of Jewish families who had recently arrived in the city. This area is between modern day Skinner Lane (on the northern boundary) Regent Street (to the east), Lady Lane (as the southern boundary) and North Street (to the west). Jacob went to Darley Street School. Now demolished, it stood where the College of Building is now.

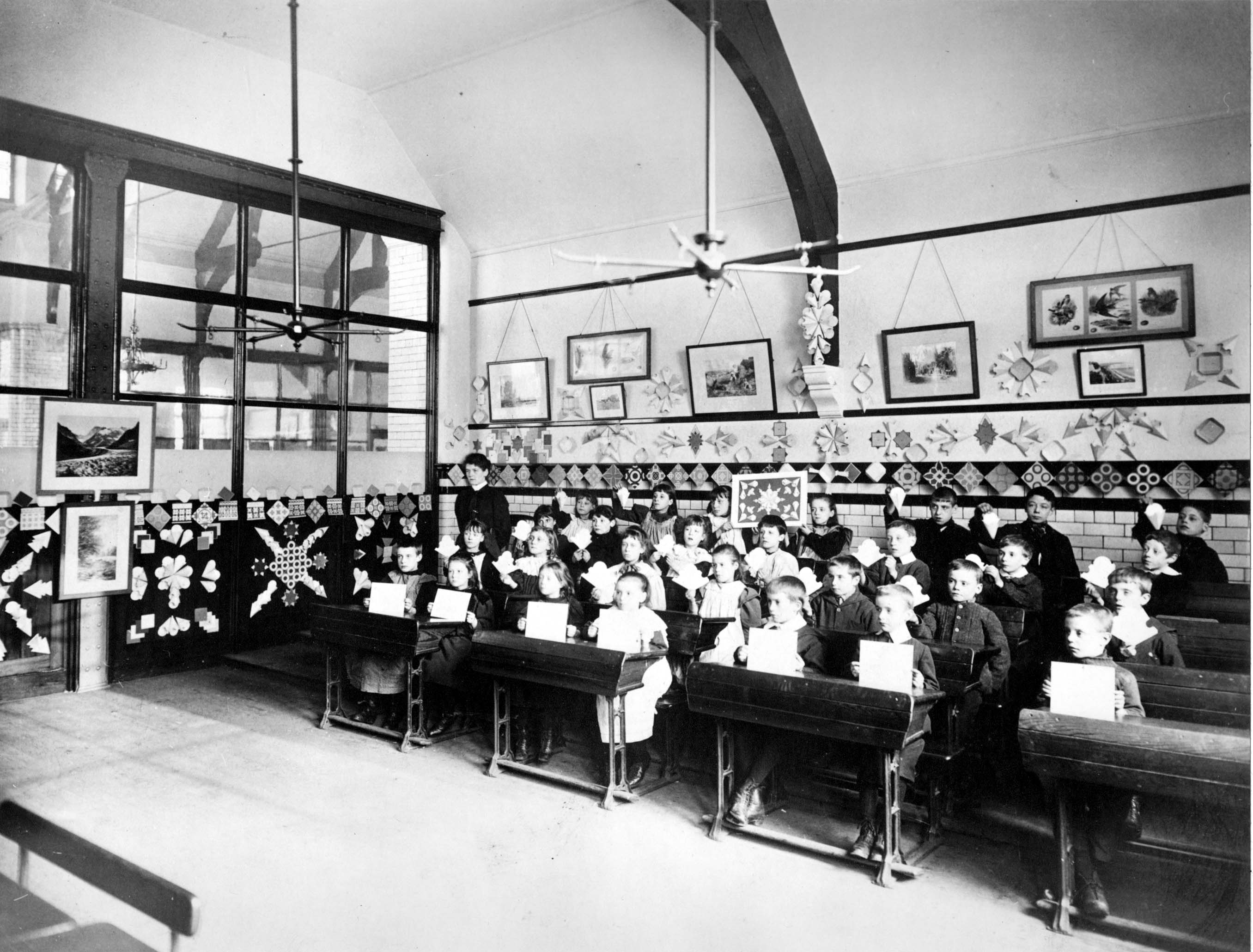

Jacob was encouraged in his art by his art teacher, Gertrude Poyzer, and the progressive Headmaster, Harry Blackburn, at Darley Street School. The image above shows pupils in Darley Street School around the same time that Jacob would have attended. The walls are decorated with children’s artwork and the pupils have been making more cardboard crafts. Jacob won bursaries to help with his art, and a scholarship to Slade School of Art, London. However, he returned to complete his studies in Leeds.

Jacob Kramer spoke to the Yorkshire Evening News in 1928, describing how, as a 13-year-old, he had run away from home:

‘I earned my first shilling after I had run away from my elementary school -

'I was at the Leeds Midland railway station [near present day Leeds Dock] when I saw a commercial traveller with some parcels of hats. I was rather strong and big for my age and offered – for the fun of the thing – to carry them for him. I took them for him to a place somewhere behind the General Post Office, and he rewarded me with a shilling.

‘My parents were rather strict and would not have approved of the escapade. I spent the shilling at a music-hall. The music-halls, with their colour and rhythm, always attracted me. I was always restless and ran away to Middlesbrough, where I worked in a municipal garden as a boy assistant, earning a few odd shillings. Then I went to Manchester, where I got a job doing photographic enlargements. I was then about thirteen.

‘My next adventure was at Blackburn, which I just managed to reach without a penny in my pocket.

'There I saw a horrible-looking shop with one or two photographs stuck in the window. I asked the proprietor if I could be of service to him and told him my story. He asked me if I knew how to do retouching work, and I said ‘Yes’, though I had never done any before. Rather surprisingly I did the work properly when he gave me some samples to try my hand on. I stayed there only a week, however, for my employer, who lived alone, fell ill, and wanted me to do housework for him, and I found this disagreeable. After another brief stay at Manchester, I came back to Leeds, got a job with a printing firm and managed to do rather well with them.’

The stories above show his tenacity, entrepreneurialism and creative spirit. He had an immense pride in his Jewish heritage, and many of his works reference his faith. However, he also recognised the struggles of being an ‘outsider’ migrating into a city following early experiences of escaping persecution and wanting a sense of belonging.

He was called up to fight in the First World Way in 1917 and fought for two years in France. Writing to fellow artist Herbert Read in 1918, Kramer said that when he looked at an object, he saw both its physicality and its spiritual manifestation.

His struggle was to escape the physical and only paint the spiritual form.

Do you see this in the works below? How? Is it the colours, the shapes, the paint?

His friend, Jacob Epstein, crafted a bust of Kramer in 1921. Epstein says of Kramer, ‘[he] was a model who seemed to be on fire. He was extraordinarily nervous. Energy seemed to leap into his hair as he sat, and sometimes he would be shaken by queer trembling like ague. I would try to calm him so as to get on with the work.’

Kramer was part of the Leeds Art Club and then started the Yorkshire Luncheon Club, who entertained many contemporary artists at Whitelocks from the 1930s to 1950s. Jacob sought out and supported an artistic community for discussion and debate.

He lived in Little Woodhouse, died 4 February 1962 and is buried in the Jewish cemetery at Gildersome.

When thinking about an artist’s work, using sensory, mindful practice is often a good way to start. Look at the artwork for longer than you usually would. Research suggests that most people in a gallery look at an artwork for 27 seconds. Try looking for 3-5 minutes. What do you actually see? Look deeply. Look slowly.

Think about the colours the artist uses – what do they remind you of? What feelings do you think he trying to convey? Think about the shapes he uses, and how he uses them. Is everything lifelike, or more abstract? What do the angles tell you? Is there repetition or flow across the canvas? What are the figures doing, thinking, saying? What do you feel when you look at the artwork? Are they heavy or light? If you could touch the angles and colours, what would they be like?