This resource is part of the Museum Snapshot collection - a collection of smaller resources perfect for starters, plenaries or spare moments to explore something fascinating.

Curriculum Links

- KS2 Science - living things, humans and other animals

- KS3 Biology - ecological relationships

Mo Koundje, known as Mok, was a Western Lowland Gorilla. His taxidermy mount is on display at Leeds City Museum, and his skeleton is at Leeds Discovery Centre.

Although we don’t know exactly he came from, we know that when Mok was young, he was taken from the wild. He could have been orphaned after his family were hunted, or he may have been captured in order to be sold as a pet. For around two years, he was kept by a French man and his Polish wife, who lived in the former French Congo (now Republic of Congo, also known as Congo Brazzaville). André Capagorry was an administrator for the French colonial government, and worked in areas of Africa which were controlled by French, before they became independent countries. Angèle Capagorry played with little Mok every day, along with another gorilla. Mok’s full name, Mo Koundje, means ‘Little Chief’. His companion was named Moina Massa, which means ‘Little Lady’. Moina was a bit older than Mok.

The Capagorrys fed Mok and Moina a diet based on their own European food, including tea, bread, eggs and chicken broth. Gorillas in the wild eat mainly vegetables, so this wasn’t a healthy diet for them. The gorillas had also been trained to use cutlery.

Mok’s life changed again in 1932, when he and Moina were sold to London Zoo. We know from archival research that they left Ouesso in the French Congo on 15 June 1932. They travelled to Berberati, probably on a river steamboat, in what was French Cameroon (now Cameroon). From Berberati, they travelled to Douala, a major port in Cameroon. In Douala, they boarded a passenger ship called the Foucauld, on 9 July. They arrived in Bordeaux in France on 27 July.

Dr Vevers, superintendent of London Zoo, met André Capagorry at Hotel des Grands Hommes in Bordeaux in the middle of August. It seems the gorillas had been staying there since their arrival in France. He paid £1,100 for Mok and Moina, and returned with them to London. This was a huge amount of money at the time, the equivalent of around £75,000 in today’s money. Zoos had not done well with keeping gorillas in captivity, and London Zoo had decided not to try it again since the early deaths of their previous gorillas. However, the chance to have both a male and female gorilla, also used to humans and European food, was seen as an opportunity too good to miss. At that point, gorillas had never bred in captivity, and London Zoo hoped that Mok and Moina might breed when they were older. They were told that Mok and Moina were around seven and eight years old when they were bought, but it became clear later that they were much younger, probably around four and five.

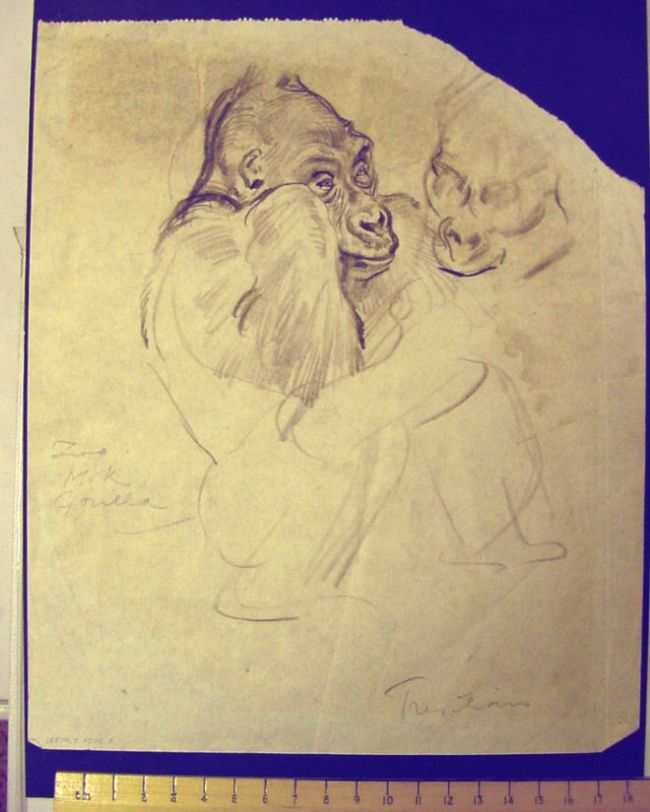

When Mok and Moina were brought to London Zoo, they were a hit with the public. Newspapers reported their arrival, and gave details of their appearance and behaviour. Photographs of Mok and Moina in the press, and in London Zoo guides, show us what Mok looked like when he was alive, which isn’t well reflected by his taxidermy mount. When they arrived at the zoo, Moina was larger than Mok, and was the dominant of the pair in their games.

In November 1932, Mok became ill with pneumonia. The staff at London Zoo were very worried, and he was nursed night and day by his keepers. The time they spent with him while he was ill mean that he became more used to his keepers, and could be handled quite easily. It is clear that they cared for him very much.

When the gorillas first arrived, they were kept in what had been the Lemur House. They were kept inside when it was cold, so wouldn’t have had much space to play in. A special new building was designed for them by Berthold Lubetkin, who later became famous for his architecture. The new enclosure gave them more space, and had lamps and heating to keep the gorillas warm. However, the gorillas still had very little freedom compared to wild conditions, and were surrounded by concrete and metal bars rather than trees and undergrowth.

As the gorillas got older and grew, Mok eventually overtook Moina in size. He then became the dominant of the pair. Moina would make a nest from straw for her naps, which Mok would then sleep in, leaving her to make another. As Mok got larger, he became strong enough to tear up radiators, break the weighing machine, and pull internal doors off their hinges. Mok and Moina were both cheeky, and had taken and even eaten a number of zoo keepers’ hats!

Mok and Moina cared a lot about each other. When they had been moved into their new enclosure, they had been taken separately. After the keepers had moved Moina, they came back to the Lemur House to move Mok. They found him with tears running down his face: he thought Moina had been taken away from him. Although they had separate sleeping areas in their new enclosure, a window was made between them so that Mok and Moina could still stay in touch during the night.

Unfortunately, Mok became ill again in the winter of 1937. He died on 14 January 1938, before reaching maturity. A post mortem found that he had died of Bright’s disease, a kidney condition also found in humans, linked to his inappropriate diet. Mok’s illness and death were widely reported in the press, and London Zoo received thousands of phone calls from concerned well-wishers before he died. While the staff at London Zoo were devastated by Mok’s death, probably no one felt his loss more than Moina. The two gorillas had been together for most of their lives, and suddenly he was gone. She died the following year.

Leeds Museums and Galleries acquired Mok’s taxidermied skin and skeleton, and put his remains on display in July 1938. At the time, there weren’t many gorillas on display in museums outside of London.

Unfortunately baby gorillas are still traded illegally, and gorillas are also poached for their body parts and meat. Their habitat is being destroyed by logging and mining, and there are far fewer than there used to be. Western Lowland Gorillas are critically endangered, and Mountain Gorillas are endangered.

Discussion Ideas

- Can you use the information to map Mok’s journey from the Congo to London? How do you think he felt on this long journey?

- When gorillas were first kept in zoos, they didn’t live very long. Why do you think this might have been?

- Do you think gorillas and other great apes should be kept in captivity today? What are gorilla enclosures like in zoos today?

- Do you think it was right to buy and sell great apes?

Find out more:

Find out more about the threats facing gorillas, or another animal. What can we do to help?